Designing wind farms is a fairly challenging task as many different environmental factors come into play impacting the energy yield. While the wind exposure of the turbines matters is the most impactful factor, a successful windpark project also needs to minimize building costs, one of which is where to build access roads. Here, the terrain plays a significant role: it's cheaper to avoid steep flanks and excavate rather longer than steeper road channels.

Together with Nordex Energy, one of the world's largest wind turbine manufacturers, we were given the task to automate the planning of roads to connect the wind turbines to each other. In this article we will focus on the problem itself, the approach we decided to take and the challenges we encountered along the way. Last but not least, we will provide some ideas for optimisation and scalability.

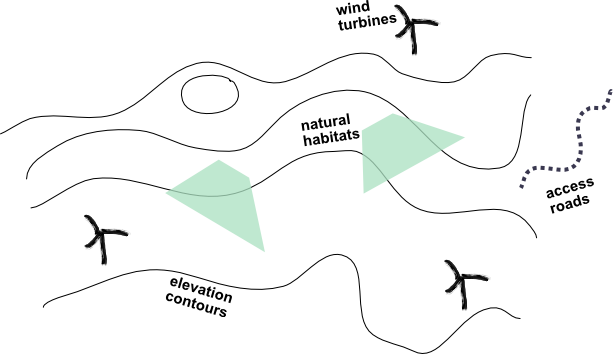

Given a set of wind turbine positions in a wind farm spread across hilly terrains including natural habitats, an existing road infrastructure and corresponding access points to the farm, the objective is to find the least cost paths connecting the turbines with each other.

Routing requires structures to traverse which are typically streets, lanes or paths. In this application however these are a scarce commodity and thus new roads will have to be built. We can make use of the terrain's elevation model (DEM), which covers the entire region and inherently can be transformed into a topological mesh which then can be used as a routable network to get from one point to another.

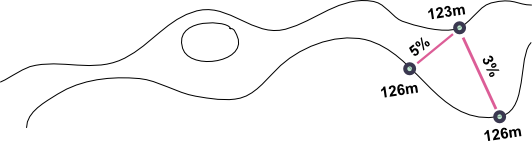

Contour lines as such represent a constant value, in our case the elevation. If one were to connect points (vertices) of neighboring curves which each other eventually a topology can be derived yielding a routable graph consisting of vertices and edges. We can hijack Delaunay's approach for triangulating a set of points to achieve this efficiently which will produce a set of non-intersecting triangles connecting neighboring contour lines with each other. Each edge of each triangle now represents a potential road segment which can be used to connect the turbines. Furthermore, we know the slope of each edge (the elevation difference between the start and end point of the edge) which we can use to calculate its cost as a function of length and slope.

At this point this graph merely knows about the elevation, i.e. shortest path algorithms will naturally avoid costly edges (steep!), so it's actually what we wanted to achieve. The reason behind is that large trucks loaded with heavy turbines will have a hard time to drive on them. On the other hand the terrain may enclose natural habitats, waterbodies or regions which additionally should be considered in the path finding between points on the map. While a lake will be a hard restriction, a rocky area may rather be penalised as it will be hard to build paved roads on. Any of these features can be described as areas which as overlays can spatially effect the base network by intersection causing a hard removal of the edge or an update of the edge cost.

The last step in the preparation of the graph is to bake roads, such as jeep tracks, which already exist into the topology. These are carefully selected by the wind farm planners and as no actual building cost is involved, the cost can be neglected for this subset of edges.

Each wind turbine in the farm is planned and sits on top of the topology consisting of interconnected edges. The question at hand is where to build the roads to minimize the cost which is influenced by the elevation and length of edges. In graph theory one may directly think of a minimum spanning tree which connects all the vertices together, without any cycles and with the minimum possible total edge cost. The problem we are trying to solve is more specific as we are looking at a subset of the vertices, i.e. we want to find the minimum tree that spans the wind turbines. A solution to this problem is known and referred to as Steiner tree which makes the problem NP-complete. Hence, there exists no known way to find a solution quickly, i.e. the time required to solve the problem increases rapidly as the size of the problem grows. With wind farms up to 50 kilometres in diameter and elevation models of 1 meter spatial accuracy the amount of edges amounts up to hundreds of millions making a "fast" solution given the Steiner tree approach unrealistic.

If we knew where to start, we could step by step connect each wind turbine to our solution. Access points to the rescue. These are entry positions, which could be existing roads, sitting at the periphery of our network. The challenge is to be able to iteratively connect them with each other in the cheapest possible way. For the sake of clarity, let's imagine 3 planned turbine positions (wt1, wt2 & wt3) in a wind farm and one access point (ap) we want to build roads to. To determine the cost for these, we can make use of routing computations which will individually yield the accumulative cost to get there (depicted in the cells of the following table).

| wt1 | wt2 | wt3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ap | 17 | 15 | 10 |

Turbine wt3 is the closest turbine to the access point with a total cost of 10, so we can pop it from the queue and continue our quest to connect the next turbine.

| wt1 | wt2 | |

|---|---|---|

| ap | 17 | 15 |

| wt3 | 4 | 2 |

Grabbing the minimum once again from the remaining unsettled turbine locations wt1 and wt2 to the settled ap and wp3, the next road will be built fromwt2 to wt3.

| wt1 | |

|---|---|

| ap | 17 |

| wt3 | 4 |

| wt2 | 8 |

Finally, we connect the last turbine wt1 to wt3 to our cheapest possible road network.

In each iteration we can go one step further and update those edges which have been traversed in the previous search. Translating this to the real world means that these roads will have already been built, i.e. the cost for construction can drop to 0 again. In our example nothing would change in this scenario, however if we would add additional turbines on top of a realistic topology consisting of millions of edges, things may look different.

In the course of this project a few promising ideas evolved to optimize the process in terms of performance. Given a wind farm project of tens of kilometers in diameter with a detailed terrain model we see room for improvement in different areas.

From the triangulated polygons using spatial operations we derive points that touch each other which become our vertices in the graph topology. Subdividing the area into regions would provide room for computing the topology in parallel which afterwards could be stitched back together with support of spatial operations.

Likewise there exists ample opportunity to run the least cost paths computations in parallel to improve the processing times. Traversing millions of edges with naive Dijkstra in sequence is a costly process. Derivative routing algorithms such as A Star or Landmark-Based Routing in Dynamic Graphs would additionally provide some computational benefit to the search guiding the algorithms in the right direction.

The backbone of this project has been developed with PostGIS and pgRouting which in combination feature a powerful range of various spatial operations and routing functionalities. The advantage here is that we can make heavy use of relational databases giving us ample opportunity to manipulate the graph topology in an easy way. In conjunction with QGIS we developed a plugin which is used as the gateway for all external data pushed to the database, such as contours, restricted areas and existing roads.